An episode from the

battle of Lutzen, 16 November 1632, by Palamedes Palamedesz (1607-38). The figure in the

centre is presumed to be Gustav II Adolf riding his white charger, Streiff, at

the head of the Smaland cavalry regiment.

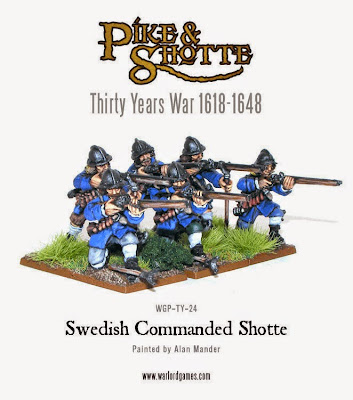

The dominant army in the Thirty Years War (1618–1648)

responsible for many military innovations, as well as establishing the first

modern professional army.

Much of northern Europe went to war in 1619 for political

and religious reasons. The Diet of Augsburg in 1555 had decreed that a prince

could mandate a particular religion within the borders of his domain. This

applied to Lutherans as well as Catholics. It did not, however, include

Calvinists. As Calvinism grew in popularity with many in the lower classes, it

also became more distasteful to many princes. In 1619 Ferdinand of Bohemia, a

staunch Catholic, rose to the position of Holy Roman Emperor. Although placed

in that position by the seven electors whose duty it was to choose the emperor,

Ferdinand had but two days prior to his election been deposed by his Bohemian

subjects in favor of a Calvinist ruler, Frederick V of the Palatinate. In order

to regain his Bohemian throne and crush the Calvinists he despised, Ferdinand

brought the power of the Holy Roman Empire to bear on Calvinists in his

homeland and on Protestants in northern Europe in general. Thus began the

Thirty Years War.

Throughout the 1620s, the Catholic imperial forces pillaged

their way through Protestant territory, the armies led by Johann Tilly and

Albrecht von Wallenstein. These two generals raised forces through force,

principally by devastating a region so thoroughly that the only alternative for

the survivors was to join the army and be paid in loot. With an army driven by

blood lust more than principle, the Catholics defeated Frederick V and gave his

homeland of the Palatinate to a Catholic monarch. They then defeated Danish

forces raised by King Christian IV that entered the war in 1625. By 1628,

however, the Catholic armies had stretched their forces too thin and ran into

trouble when attempting to besiege the port city of Stralsund on the Baltic

Sea.

A few days prior to the beginning of the siege, the city of

Stralsund concluded a treaty with Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus. Gustavus’s

army was the best of its era and was molded completely by its commander. With

this army, Gustavus acquired the provinces of Estonia and Latvia after

defeating the forces of both Poland and Russia between 1604 and 1617. It was an

army unlike any other of its day, and Gustavus embarked for Stralsund to both

protect his newly acquired provinces and to fight for the Protestant cause.

The armies of Europe at that time were primarily mercenary.

The core of the force typically consisted of professionals who hired out their

services, while the rank and file would be whatever manpower could be obtained.

Such an army was therefore lacking in discipline and cohesion, but if well led,

could be devastating. Gustavus, however, created his army strictly from Swedes,

and did so by mandating that every tenth man in each parish was liable for

military service. This created a national army of citizen-soldiers such as had

not been seen in Europe since the fall of Rome. It was also the first standing

army since the Roman Empire, for Gustavus kept 20,000 men under arms at all

times. Seventy percent of Sweden’s budget was dedicated to this army, and it

was one of the few armies of the age regularly and fairly paid. Gustavus

instilled in his men a spirit that combined nationalism and religion, and it

was an army that was motivated, disciplined, well prepared, and well equipped.

Although all the armies of the seventeenth century were

equipped with firearms, Gustavus improved his weaponry with mobility in mind.

The standard formations of the day were large squares based upon the system

developed by the Spaniards some decades earlier. The standard square was made

up of a mixture of pikemen and musketeers, who used a heavy wheel-lock musket.

The Swedish musket was redesigned by Gustavus to lighten it from the standard

25 pounds to a more manageable 11 pounds. This made the standard forked support

used by other armies unnecessary. He also created the cartridge, a paper

package with a premeasured amount of gunpowder and a musket ball. This made for

much quicker reloading, hence much greater firepower. The musketeers were

deployed in ranks six deep, unlike the 10 ranks used in other armies. The front

three would face the enemy with ranks successively kneeling, crouching, and

standing. They would volley fire, then countermarch to the rear to reload while

the other three ranks moved forward to deploy and fire. Although the standard

formation of other armies called for a greater number of pikemen to act as

defenders for the musketeers, the Swedes introduced a 150-man company that

included 72 musketeers to only 54 pikemen. The smaller company could be used

much more flexibly than the large square formation.

Gustavus also improved his artillery. Most guns of the time

shot a 33-pound ball and were so heavy that they were arranged to stay in one

place all day. The Swedish artillery was much lighter. Most fired only six-or

12-pound balls while the smallest (which could be easily moved by a single

horse or three men) fired only a three- pound ball. Constant training that only

a standing army could provide made Gustavus’s artillerists able to fire their

cannon eight times while the enemy musketeers could fire but six times in the

same span. Again, this meant increased fire power for the Swedes. By quickly

moving light field pieces around the battlefield and using smaller infantry

units to outflank the bulky enemy squares, the Swedish rate of fire was

designed to take advantage of the large target the enemy formations presented.

Finally, Gustavus remolded the cavalry. The standard

European horseman was little more than a semimobile gun platform. He would ride

to a position on the battlefield, usually on the flanks of the infantry

squares, and deploy with the same large musket the men in the squares carried.

The cavalry was trained to fight in much the same fashion as Gustavus’s

infantry, with a line of horsemen delivering a volley of pistol fire, then

riding to the rear to reload as another line advanced. The Swedish cavalry was

again more lightly armed, with carbines (shortened muskets) and pistols. In the

early years of his reign, Gustavus’s cavalry fought as dragoons, mounted

infantry who dismounted to fight in order to capture positions before the

arrival of the infantry. In later times they were equipped with sabres and

fought from the saddle. The Swedish horsemen would charge the enemy cavalry,

which had to maintain its formation in order to maintain its fire, and the

speed and shock of the Swedish assault shattered whatever cohesion the enemy may

have had. Then the close-range pistol fire, coupled with the cold steel of the

sabres, proved more than most horsemen could withstand. The coordination

necessary among cavalry, infantry, and artillery only came from the constant

training that a regular standing army could provide.

All of this fire power and coordination needed direction,

however, and Gustavus provided that as well. He proved himself in battle (which

always endears men to their leader) but ruled his army with an iron hand.

Unlike the pillaging and looting encouraged in the armies of Tilly and

Wallenstein, the Swedish army was banned from any action against civilians.

Hospitals, schools, and churches were strictly off-limits as targets. Anyone

caught looting or harming a civilian was punished by death, the sentence for

violating about a quarter of Gustavus’s regulations. Gustavus apparently

believed that if one fought for religious reasons, one should behave in a more

religious manner.

Thus, it was a thoroughly professional army that Gustavus Adolphus

brought to the continent to assist the city of Stralsund in 1628. Although he

was forced to recruit replacements while on campaign, he tended to hire

individuals and not mercenary units. This brought the new man into an already

organized unit with an existing identity, and he became part of the Swedish

army rather than remaining a part of a mercenary band. The Swedes arrived on

the coast of Pomerania in 1630 but, rather than welcoming them, the

hard-pressed Protestants viewed Gustavus’s forces at first with suspicion. In

the fall of 1631, Gustavus finally found an ally in the Elector of Saxony, and

in September the allied force met and defeated Tilly’s imperial force at

Breitenfeld, near Leipzig. In three hours, the entire momentum of the war was reversed.

Thirteen thousand of Tilly’s 40,000 men were killed or wounded, and the army of

the Holy Roman Empire fled, abandoning all their artillery. This victory helped

unite the Protestants into an army that numbered almost 80,000 by the end of

the year. The following spring, Gustavus defeated Tilly again, and the imperial

commander died of wounds a few weeks later. The Protestant army liberated much

of southern Germany, but in the process extended their supply lines too far.

Wallenstein took advantage of this by moving a new army into Saxony,

threatening Gustavus’s rear. Wallenstein occupied a strongly fortified position

at Alte Veste, which the Protestants failed to take after a two-day battle in

September 1632. When Wallenstein dispersed his men into winter quarters in

November, Gustavus seized his opportunity and attacked with 18,000 men against

Wallenstein’s 20,000 at Leuthen, about 20 miles from Breitenfeld. Again the

forces of the empire were forced to retreat, but Gustavus was killed in the

battle.

Command of the army fell to Prince Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar,

who led it during the majority of the battle at Leuthen, but Gustavus was

irreplaceable. Luckily for the Protestants, however, Wallenstein failed to

follow up on the advantage of having killed Gustavus. Instead, he entered into

a variety of political machinations that ultimately lost him his job and then

his life. With the deaths of Wallenstein and Tilly, the empire’s armies became

the norm, and civilians remained out of the way of the battlefield until the

nineteenth century. Nationalism, which had been growing for 200 years, began to

take serious root in Europe. Gustavus Adolphus’s professional military was the

standard by which others were created until the development of the completely

nationalist armies engendered by French Revolution.

References: Addington, Larry, Patterns of War through the

Eighteenth Century (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1990); Roberts,

Michael, Gustavus Adolphus: A History of Sweden, 2 vols. (New York: Longman, 1953–1958);

Wedgewood, C. V., The Thirty Years War (Gloucester, MA: P. Smith, 1969 [1938]).

No comments:

Post a Comment